As the year starts and the social discourse shifts to focus on resolutions, plans, and goals for the next 12 months, the pressure to define and name everything that my energy will go toward this year feels like a familiar but baffling phantom constantly following me, leaning its full weight over my shoulder, watching and criticizing. There’s nothing inherently wrong with identifying areas to develop or interests you want to focus on, but in our society, there's a quick and slippery slope from motivation and structure to moralizing and stress. For much of my adult life, I found such external prompts really valuable. As someone with ADHD, sometimes I need a reminder to pause and consider, “Wait…is this what I want to be doing?” so having a reason to reflect, recalibrate, and set intentions about the direction I’d like to go has often been helpful (once I learned to do so in a more open-ended and flexible way). Plus, who doesn’t like the feeling of a clean slate?

But the once freeing, purposeful feeling of this undertaking now involves intense and exhausting efforts to create and cultivate possibilities and hope in new places as the old, familiar and preferable options continue to fade away. This is complicated by having to wade through and simultaneously carry the sticky, suffocating weight of all I have not done, cannot do, will not accomplish, and will have to sacrifice just to make it through another year - thanks largely to Long COVID making my world small and the lack of effective public health response to the still circulating virus making it even smaller.

Thinking about the appeal of a “clean slate” reminds me of this really powerful - and visually stunning - piece that used brushstrokes to depict the symptoms and experiences of Long COVID. Some of us are longing for a blank canvas, to be able to put everything else behind us and just focus on making a beautiful masterpiece of a life. How nice it would be to make choices and use brushstrokes to give shape to the dreams and hopes we have for ourselves. What a difference it would make to be unburdened by areas that got a little heavy and instead just rework them until they match the image in our mind’s eye. But instead of intentional movements toward a cohesive, satisfying composition of art that others will applaud and appreciate, the best many of us have to work with are reactive, haphazard flailing attempts at messy survival, which creates a picture that’s often met with judgment and disdain.

To work with a blank canvas, with carefully laid plans, and with all you need to bring your creation to life does require intention. It also involves - among other things - substantial privilege/s. I’m still coming to terms and reckoning with how much this is true. This lens is something I had a vague sense of before becoming chronically ill and disabled, but this truth is now something I know and feel in immeasurable ways and see everywhere I look. It’s been one of the many (no pun intended) mini “red pills” to come after nearly 5 years down the rabbit hole of Long COVID.

I suppose there’s nothing quite as effective as becoming disabled to open someone’s eyes to all the micro and macro flavors of privilege and ableism baked into our world. I wonder, and worry about, how many people will need to learn this the hard way and personally experience true loss of health and ability to really comprehend the limits of personal agency.

I imagine this lack of first-person, experience-based insight is one of the biggest contributing factors in why such realities are so hard for many people to grasp. I believe the inability to recognize ableism is also why so many familiar, inane, and baseless platitudes get recycled and become extra popular this time of year as everyone starts setting goals and making resolutions. I want to deconstruct a few of the ones I’ve encountered already.

“Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

I just saw this comment on the post of someone who has been open about having a terminal diagnosis and shared further concerning updates. I’ve also seen similar invalidating comments on the posts of devastated, desperate people who have lost their homes and everything they’ve worked their entire lives for in the L.A. wildfires. *insert the heaviest sigh and eyeroll here* Look, I understand that when people express sadness or deliver bad news, it’s a common and even natural response to want to make them feel better. So often, such words only serve to make the person saying them feel better. Among marginalized communities, chronically ill and disabled folks, or those who are grieving or in crisis, it seems pretty rare to find people who are actually comforted by trite sentiments that bypass the pain or complexity of a situation. They may be looking for substantive help, or if not, at least to have their experience witnessed to feel supported. Often, well-intentioned optimism like this ends up being dismissive and invisibilizing.

This is aside from the fact that statements like this imply that all someone needs to do is want something bad enough for it to become…I don’t know…magically true? Many people miss the insinuation that if there isn’t “a way” or “a solution”, that the person must be lacking in their determination or character. Another version of this is when it’s suggested, or outright proclaimed, that someone’s problems are due to their lack of faith or sins. (More on this distorted interpretation and spiritual abuse tactic another time.) The fact of the matter is that bad things happen to good people, there are situations where things cannot be fixed, and problems exist that people cannot solve or at least cannot solve alone. Sometimes all the “will” in the world cannot provide “a way” out.

This platitude and many others serve to maintain the illusion of control, or overestimating one’s control over outcomes, which many people’s existential framework and self-soothing mechanisms are based on. Being in control and capable of changing things is often really comfortable and preferable for a lot of reasons, so to some degree it makes sense that people desire for this to be true and might default to assuming this. However, being unable to recognize the limits of what someone is able to control can lead to some stealthy distorted beliefs that can really take a toll, particularly with the other side of this coin. There can be a slippery slope to shame from “I can control and change things in my life, it’s just a matter of finding the right way to do it” to “If I’m in control but it isn’t fixed, I must be to blame”. Sometimes this develops or gets reinforced when someone has been the scapegoat in their family, or gets frequent messages that they are to blame. This also plays out unconsciously when people learn early in life that they need to “control” or maintain the status quo to prevent harmful or hurtful behaviors from others, or that to keep relationships stable/avoid abandonment they must “control” or change themself to meet the needs of the situation or person.

People also repeat and internalize what they see and hear. Consider for a moment all the various ways in which our culture conditions us, through bootstrap mentality/morality practices and platitudes like “where there’s a will, there’s a way”, into believing if there is a problem, 1) it’s the person’s fault since not everyone has this problem, 2) there’s obviously a solution or something that could have prevented this, otherwise they probably deserve it.

Dangling those two carrots is a pretty effective way to convince a population they need to buy more products and consume more things, for which they need to earn more money by laboring for someone else, who profits off selling another product to someone else with the same carrots dangled in front of them.

If we weren’t sold the illusion of control, how much less would people consume? How much more would people focus on the roots and rotten frameworks of problems instead of looking for individualized fixes?

When we take on the full responsibility of complex or manufactured problems, many times we set ourselves - and others - up for failure in numerous ways. We often expend time, energy, and money on fruitless pursuits that leave us feeling worse when we fail the impossible task. It can impact people’s self-talk by contributing to “I’m not ___ enough” or “I’m too ____”. This can also reinforce a pattern of assuming all problems are always a personal failing and one’s own fault, which can make us feel worse when internalized over time. Such beliefs also end up coming out sideways when we project this belief onto others, including through empty platitudes in which the subtext is “you just have to try harder” or “you wouldn’t be in this position if you did something differently”.

“What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger.”

“We all have the same number of hours in the day.”

I’m going to tackle these piles of garbage together because I can give some illustrations that apply to both and to Long COVID. First a quick bit of history and context: I’m approaching 5 years of living with this condition, and I’ve lost count of the number of specialist visits, blood tests, imaging tests, ad hoc “treatments”, and various types of therapies I’ve had in that time. I did the math somewhere around 2021-2022 and had already spent over $20K out of pocket - not including the insurance premiums I also pay as a self-employed person. I’m not sure what that number is up to now, but I have nothing to show for it except a diagnosis for a condition that’s still not understood and that has no approved treatments. I’ve tried every treatment I’ve been offered, and numerous others that I’ve researched on my own and tried because they helped some people with Long COVID. MOST of both have been out of pocket costs that aren’t covered by insurance. Depending on which option we’re talking about, improvements have varied between none, minimal, short-term, only somewhat stabilizing some symptoms, helpful until it became inaccessible, or helpful until a reinfection made all my symptoms worse again and gave me new ones.

All of which is to say that, I suppose, I’ve had a lot of will (along with some privilege and luck accessing doctors and treatment options) and still not found a way to get better.

After 5 years of trying everything within my capacity and not improving, I’m still only able to work 12-15 hours a week, and I’m only still employed because I work for myself. Despite the flexibility and control I have over my workload, I estimate Long COVID has led to at least $150K in lost income since I got sick. In order to keep working part-time, I have to allocate almost all my energy to work, managing my health, and basic daily life tasks. Socializing, already complicated by the lack of public health policies or clean air initiatives, has to take a back seat. Recently, a virtual physical therapy appointment that was scaled back to 20 minutes of light stretching sent me into a crash where I had to stay horizontal for a couple days.

So leisure activities or hobbies? Forget about it. I have only recently been able to incorporate a little bit of embroidery. The other night, I struggled to complete a short DuoLingo Spanish lesson when I got (without exaggeration) at least 30-40 exercises incorrect in a row. Early in the pandemic before my symptoms and baseline worsened, I decided to rehab my black thumb and got several plants. A few months ago I lost several of my favorite ones that I had kept alive the longest because they got infested with pests and I didn’t have the energy to give them the attention they needed until it was too late. I’m about to lose a few more.

What “doesn’t kill us” sometimes makes us substantially weaker, less able to survive in a capitalist society, and struggle to scrape together some quality of life to get by. Sugarcoating and sanitizing people’s experiences of immense loss to make them inspirational is one of the things I find most offensive as a human, and most harmful as a mental health professional. Implying there is something wrong with people who cannot or do not turn their grief and pain into something palatable and TedTalk-worthy is toxic positivity at its worst.

If you’ve been made stronger by your struggles, congratulations. I’ve had experiences where that was at least partially true, too. But chronic, intractable Long COVID? As I recently described it, “It changes you on a cellular level, steals your independence, rips apart the fabric of all your relationships, demolishes your sense of identity, and changes how you trust and interact with yourself, others, and the world at large.” When something like this happens, along with several other chronic conditions, there’s no part of your life it can’t touch, including the “number of hours in your day”.

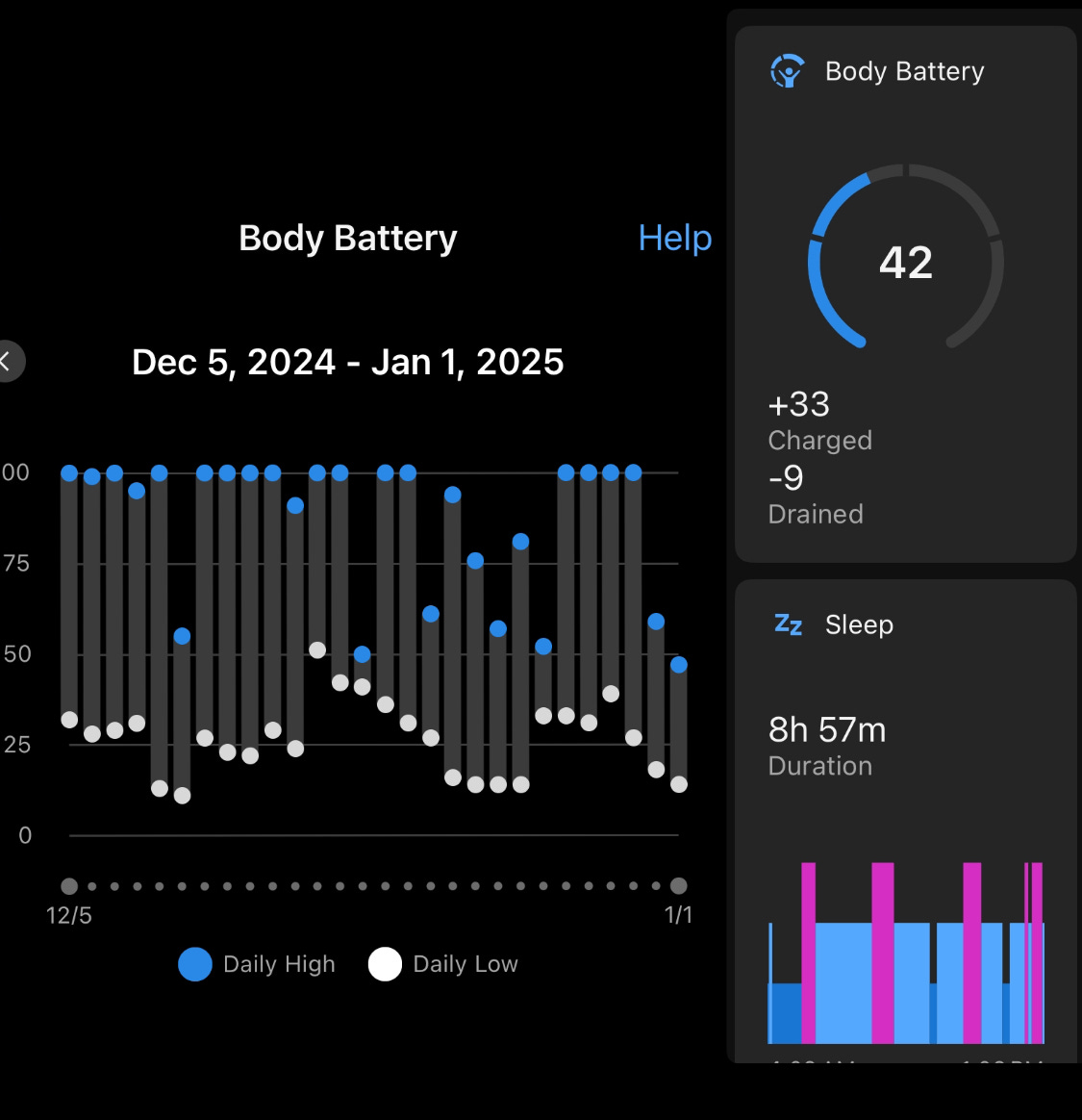

A few months ago, after hearing how helpful they have been to other folks with Long COVID, I decided to invest in a *used* (thanks, Poshmark) Garmin smart watch. This measures biometric data that can be helpful when trying to pace energy, physical, and emotional exertions to avoid post-exertional malaise (PEM) and post-exertional symptom exacerbation (PESE) to avoid crashes. It took awhile for the readings to calibrate to my body, but in the last month or so they have started to be helpful.

Before I paint this picture, I want to mention that every experience of Long COVID is different. I’ve known some people whose batteries never charge beyond 30%, and how this illness impacts people can vary widely. For me, a 100% battery charge now feels (at absolute best) like 50% of my pre-COVID battery, and much of the time it feels closer to 30-40% of my pre-illness capacity. On my best days that I’m “at 100%” I still feel physically ill, which can vary from feeling like an achey flu, to a hangover, to food poisoning, to having pulled consecutive all-nighters. On bad days, it can feel like all of these combined, with a migraine and/or my heart pounding through my chest and on the verge of passing out - though this is now rarer. But to prevent this, I have to carefully pace all forms of exertions - cognitive, social, emotional, physical, and taking in sensory stimuli - because all these buckets drain the same well and draw from the other buckets. Even after 5 years of multiple treatments, rehabilitation attempts, and various therapies. And thanks to Garmin, I am now starting to be able to convey how challenging this is to do (despite also developing a mild allergy/contact dermatitis from the watchband, thanks to Long COVID-induced mast cell activation syndrome).

I’ve noticed that if I over-exert and drain my “body battery” below 25%, I will both feel physically ill in the moment, AND no matter how much rest and sleep I get that night, my battery will not fully recharge. If I sleep 6 hours or 10 hours, it doesn’t make a difference - my body will take days to fully recharge, and that’s only if I do not keep dropping below 25% every day - which gets to be exceptionally hard. (Yes, I’ve had a sleep study and seen 2 sleep neurologists, and no I don’t have sleep apnea or any other sleep disorders. This is just life with Long COVID.)

Recently, after overdoing it the day before, I woke up and found my body battery had only charged to 47%. I walked to the kitchen, made a cup of coffee, and got a yogurt from the fridge for breakfast. I was winded as I sat down for breakfast, looked at my watch, and my battery had already ticked down 15 points to 32%. On bad days, everything is also exceptionally more draining. I’d only been out of bed for 10-15 minutes and still had my whole day ahead of me. All my plans to do chores and get caught up on administrative work got scrapped because I only had 7% of “usable” body battery left for my entire day. I didn’t want to keep compounding the damage, because that is how some people with Long COVID and ME/CFS end up with lower and lower baselines, sometimes becoming bedbound, which can be permanent or extremely difficult to come back from.

In this case, I spent basically the whole day horizontal, aside from using the bathroom and eating easy meals. Doing “nothing” usually keeps the battery steady or it might increase 2-4% an hour. It might even continue to decrease if I’m watching or reading something intense, exciting, or stressful. My body doesn’t have a chance of really recharging in my waking hours. And again, even a good night’s sleep isn’t guaranteed to be effective, nor is it a healthy-person’s 100%. It’s really tenuous to try to avoid PEM/PESE or prolonged days of low battery, especially when, in practice, only 75% is usable on your best days.

To make things more interesting, how much energy an activity takes can vary wildly from day to day. A few days ago, I had a 100% charge after several consecutive days of being careful with pacing and getting good nights of sleep. When I got a grocery order delivered, I walked down 1 flight of stairs, carried heavy bags back upstairs, and put the groceries away. This ticked down my battery from 80 to 64% - almost the same drain as what making a cup of coffee did a week ago. On this “good day” I was lucky I still had 39% charge left to work with for the day, but a lot of that went to showering and trying to plan out some semblance of a schedule for the week. The amount of planning required to pace and try to space things out is almost as frustrating as the energy drain it requires. And this is far from the only condition that has such an impact on people.

So, I ask you…do we all have the same number of hours in the day? Do people with chronic illnesses or disabilities have the same number of hours as healthy, able-bodied peers? Does someone who needs to work 3 jobs to support their family have the same number of hours in the day as someone who has a people to support them at work, or help out at home? Do people who have to spend hours every day commuting via public transit have the same number of hours in the day as someone who can afford to live close to work or drive/take a rideshare to commute? There are numerous things that impact how many actual “hours in the day” someone has, as well as what they are able to do with it, especially if they have to contend with challenges that have done the opposite of “make them stronger”.

And lest anyone interpret all this as my being defeatist or fatalist…none of this is to say having intentions or encouraging ourselves toward change is pointless, nor am I suggesting we have no influence in our lives. On the contrary, I think it’s incredibly important both to define and stay close to what values and purpose provide meaning and motivation, and to find the spaces and opportunities for agency that we do have. It’s crucial to do all of this with realism and context, but doing so is hard when caught up in all the hollow advice that circulates this time of year that oversimplifies complex realities, often contributes to negative self-beliefs, and can distract and disillusion us.

Some questions for reflection:

-How have I internalized “where there’s a will, there’s a way”, “what doesn’t kill you makes you stronger”, “we all have the same number of hours in the day”? How are these influencing me, my self-talk, or expectations of myself and others?

-Am I taking on responsibility for problems that are manufactured or outside my ability to control? Where or how have I been encouraged to do this?

-Which problems are ones I actually have interest, responsibility, and/or agency to influence?

-Which ones are areas that would be better addressed with acceptance, OR a better balance of effort, acceptance, and shared responsibility/support?

-If there’s an area where I recognize I don’t actually need to try harder, what would I like to do instead with that energy, money, or time?

A note to my subscribers: It’s been a year since I started this Substack! Perhaps this post might help explain why I’ve not been able to write as much as I’d hoped to. The first day I started working on this piece about 2 weeks ago, I wrote over 1000 words in probably 4-5 hours. In that time I watched my battery drain from 80% to 36% just from writing before I had to stop to conserve some energy for the rest of the day. It’s taken several more days and at least 15 additional hours to finish this. With the reality that I need to prioritize either tasks that earn money or conserve energy, it’s been challenging to navigate this space. I feel immense guilt for not producing more for the handful of paid subscribers I have, and yet I understand why I don’t have more with how little I’ve written. I hope that might change this year, but I cannot guarantee it…but I do have some new and exciting things I’m eager to share soon.

In any case, thanks for sticking around, and enormous thanks to those of you who have supported this endeavor, and me, financially. May we all find some pockets of joy, strength, and respite in the year ahead.